Transitional justice between Peace, Memory and Reconciliation: Lessons from the Past for Syria’s Future

BY: Roberta Lazzaro Danzuso

The persistent dilemma confronting post-conflict societies concerns the sequencing of transitional imperatives. When should the attainment of peace be prioritised, and when should demands for justice prevail? The Syrian conflict, like other instances scrutinised within the transitional-justice literature, has wrought not only material destruction but also an erosion of social trust and communal cohesion. Consequently, tensions emerge between imperatives of negotiated stability and claims for accountability for grave international crimes[1].

This article interrogates the enduring tension between peace and justice in post-conflict transitions and applies comparative lessons to Syria’s emerging transitional architecture. Building on insights shared by practitioners and scholars during the PILPG[2] 2025 Peace and Negotiation Summer School course, dedicated to the Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, it draws on cases from Sierra Leone, the Balkans, South Africa, Colombia and Rwanda, demonstrating that durable transitional outcomes require a context-specific mix of judicial and non-judicial instruments, domestically anchored design and strategic sequencing.

Conceptual framework: instruments and sequencing

Transitional justice is not merely an alternative to ordinary criminal justice; rather, it encompasses a spectrum of judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, with varying degrees of international involvement (or none), including individual prosecutions, reparations, truth-seeking mechanisms, institutional reform (comprising vetting and removal from office) or combinations thereof, depending on the context.[3] The literature identifies several potential trajectories: privileging peace; prioritising justice; pursuing a “peace with justice” or experiencing a growing judicialization of peace processes – that is, the increasing influence of courts and judicial bodies on political negotiations, with ambivalent consequences for accountability and for the prospects of reaching and sustaining peace.

Sierra Leone and the coexistence of restorative and retributive mechanisms

The protracted civil war in Sierra Leone, partly a spillover from the conflict in Liberia and heavily fueled by the struggle to control diamond resources, illustrates the practical and moral challenges of balancing the imperatives of immediate peace with the demands of criminal accountability. The 1999 Lomé Peace Agreement included a blanket amnesty clause that facilitated a ceasefire but simultaneously left deep wounds and sparked considerable controversy over questions of justice. In practice, the transitional response was dual and parallel: a Truth and Reconciliation Commission with a restorative and narrative mandate, tasked with collecting testimonies, documenting violations and fostering processes of reconciliation; and the Special Court for Sierra Leone, established to prosecute those bearing “the greatest responsibility” for the gravest crimes (a mechanism that avoided blanket impunity without derailing the fragile peace process.

This experience demonstrates that the coexistence of restorative (TRC) and retributive (Special Court) mechanisms can succeed when their mandates are clearly delineated and communicated, when practical coordination is ensured (procedural sequencing, witness protection, allocation of resources) and when meaningful space is created for both symbolic and material redress for victims. Ambassador Yvette Stevens and other observers have emphasized that this multi-dimensional approach, together with the clarity in the distribution of responsibilities between commission and court, was central to preventing the Lomé amnesty from devolving into a perceived culture of impunity in Sierra Leone.[4]

Memory, symbols and institutional confidence in Montenegro and the Balkans

If the Sierra Leonean experience illustrates the delicate balance between peace, truth and accountability in a context marked by resource-driven conflict, the post-Yugoslav Balkans, and particularly Montenegro, highlight a different but equally crucial dimension of transitional justice: the reconstruction of trust in the aftermath of mass atrocity and the role of institutional, symbolic and economic measures in shaping reconciliation and state-building. The post-1995 Balkans demonstrate that collective traumas (Srebrenica above all) rapidly erode social trust, and that if civic culture and historical memory are not actively nurtured, the reconstruction of confidence becomes a project spanning decades.

The Montenegrin case is particularly instructive, as it combined political, symbolic and economic elements: the decision – controversial yet strategic – to introduce the Deutsche Mark at the end of 1999, and subsequently the euro, was not merely an economic maneuver to stabilize prices and safeguard savings, but also a political act of symbolic autonomy vis-à-vis Belgrade. The subsequent Belgrade Agreement and the constitutional framework established in 2002 created a pragmatic arrangement of “one State, two economic systems”, which allowed for the functional separation of economic and political spheres during the transitional period. Igor Lukšić, a key actor in Montenegro’s transition, has emphasized the importance of early confidence-building measures, predictable institutional rules and political symbols capable of ensuring minority inclusion, thereby pre-empting historical revisionism and competing narratives.[5]

The Montenegrin experience suggests that economic and symbolic measures (currency reform, autonomous fiscal policies) can serve as instruments of political stabilization, provided they are coupled with institutional reforms and underpinned by a minimal consensus on clear and predictable rules.

Alternatives and trade-offs from South Africa, Colombia and Rwanda

Whereas the Sierra Leonean and Montenegrin cases shed light on, respectively, the balance between peace and accountability and the role of economic-symbolic measures in rebuilding trust, a broader comparative perspective highlights further variations. Other transitional contexts (South Africa, Colombia and Rwanda) offer additional insights into how different societies have sought to reconcile truth, accountability and reconciliation through distinct institutional and culture mechanisms.

In South Africa, the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission – led by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and his colleagues – adopted the mechanism of conditional amnesty in exchange for full public disclosure. The public revelation of truth was conceived as a form of symbolic healing, essential for the moral legitimacy of the new democracy, even as it left unresolved criticisms regarding the lack of material punishment.

In Colombia, the 2016 peace accord introduces the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), which provides alternative sanctions and reparative measures for those who acknowledge responsibility. This pragmatic model of compromise sought to maximize truth-telling, victim participation and the reintegration of former combatants, while in many cases avoiding traditional custodial sentences.

In Rwanda, the Gacaca courts – deeply rooted in local communal practices – enabled the mass processing of genocide-related cases in a relatively short period of time, fostering community involvement and testimonial exchange. Yet they also attracted criticism for shortcomings in procedural safeguards and for the tensions they generated between local justice and international legal standards.

Comparative synthesis: no one-size-fits-all

Taken together, these cases underscore a crucial lesson: there is no “one-size-fits-all” model of transitional justice. Instruments such as conditional amnesty, alternative sanctions and community-based justice must be tailored to the cultural fabric, institutional capacity and expectations of victims in each specific context. As Ambassador Amina Mohamed has stressed, no matter how urgent a political settlement may be, peace will falter unless it is built on a foundation of inclusivity and accountability.[6] Above all, local legitimacy and victim participation emerge as non-negotiable conditions for the durability and credibility of transitional outcomes.

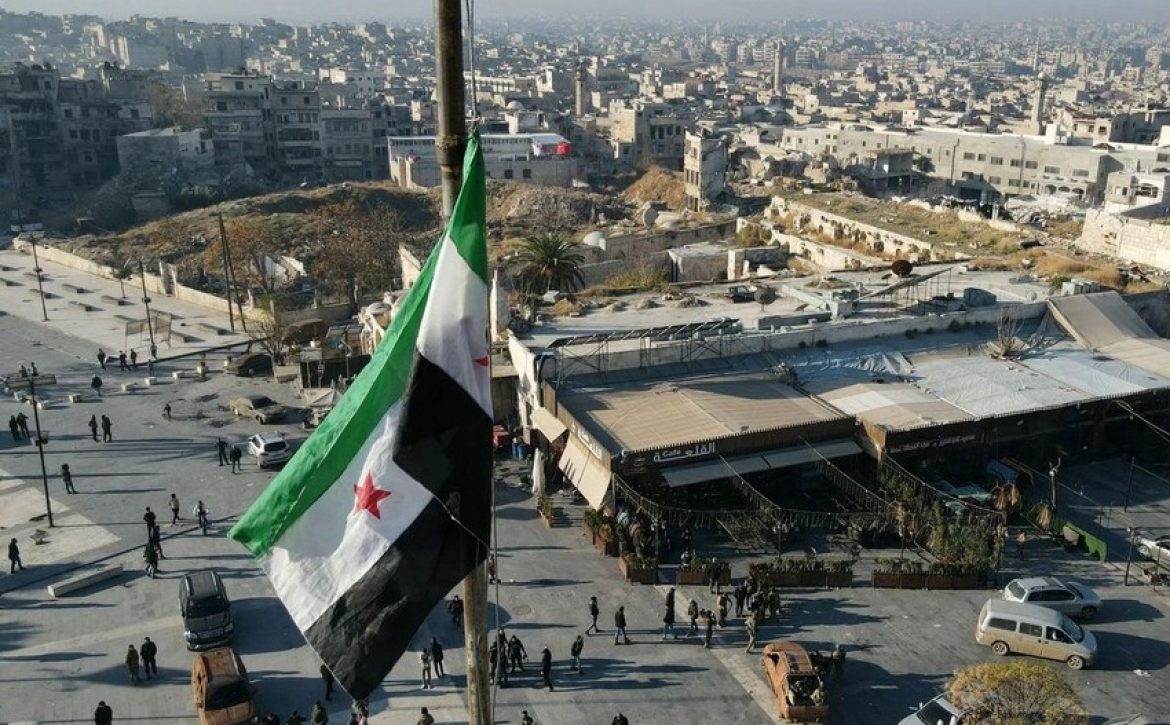

Syria: context and recent institutional developments

Today, Syria stands at a critical juncture between continuity of established practices and the opportunity to innovate a genuinely domestic transitional justice process. In May 2025, transitional authorities established a National Transitional Justice Commission (NCTJ) – mandated to “uncover the truth about the grave violations caused by the former regime, hold those responsible accountable in coordination with the relevant authorities, compensate the victims, and consolidate the principles of non-repetition and national reconciliation” – and a Commission for Missing Persons (NCM) to address over one hundred thousand missing and detained persons. As stated on Amnesty International’s official website, between 2011 and 2024, it is estimated that over 100,000 individuals were subjected to enforced disappearance in Syria.[7] The overwhelming majority were forcibly disappeared by the Assad government within its extensive network of detention facilities, while additional cases have been linked to armed opposition groups.[8] These data clearly underscore the existence of a profound vacuum that must be addressed within a transitional justice process which, as emphasized by relevant international actors, such as Amnesty International and the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), requires transparency, independence and meaningful victim participation.

Syria: sequencing and policy design

Turning these bodies into credible mechanisms demands careful sequencing and a calibrated mix of measures. The ordering of elections, judicial proceedings, refugee returns, and institutional reforms is not neutral: comparative experiences from Sierra Leone and Colombia illustrate that truth-telling, graduated sanctions and non-custodial measures are effective only when paired with credible demobilization and reintegration strategies. At the same time, some grave crimes will demand formal judicial accountability; restorative or administrative measures cannot substitute for prosecution where atrocity crimes are implicated. As the United Nations has emphasized, any transitional-justice process must be nationally owned and sensitive to local conditions, centred on victims’ needs and inclusive of all relevant stakeholders (notably women, youth and minorities).[9] Thus, international actors should support the domestic design and implementation of context-specific, victim-centred processes that address the root causes and structural drivers of violations and thereby contribute to prevention, sustained peace, development and reconciliation.

Syria: memory, participation and legitimacy

Memory and truth are inseparable from institutional capacity: the Balkans and Rwanda demonstrate that public narratives require documentation, witness protection and educational initiatives to prevent revisionism. As Joud Monla-Hassan stresses, transitional justice must be genuinely “Syrian-led”, informed by survivors, civil society and the diaspora[10]; only through meaningful inclusion can the new commissions build legitimacy and public trust. This point is salient given that the transitional authorities’ own legitimacy may be contested: the commissions must therefore demonstrate independence, transparency and representative composition from the outset if they are to earn popular confidence.

Timing and constitutional framing

Finally, Dr. Paul R. Williams emphasizes the complexity of rebuilding political, legal and social infrastructures after decades of dictatorship and conflict, noting that a return to the pre-war status quo is neither feasible nor desirable. Williams stresses that processes such as refugee returns, elections, establishment of legal mechanisms and institutional stabilization must be carefully coordinated.[11] The transitional period should be time-bound, governed by an interim constitutional framework and guided by a clear public roadmap. Strategic sequencing of these measures is essential, as holding elections prematurely, without an appropriate political and legal foundation, risks creating power vacuums or undermining democratic legitimacy.[12]

Practical recommendations

Building on comparative lessons and the Syrian context, five practical priorities emerge: 1) codify the mandates and legal safeguards for the NCTJ and NCM to guarantee independence and victim-centredness; 2) adopt a publicly negotiated sequencing roadmap that sequences elections, accountability measures and refugee returns by political feasibility and security considerations; 3) design a calibrated mix of judicial and non-judicial instruments, including hybrid or internationalized modalities for the gravest crimes; 4) mainstream psychosocial support, reparations and service delivery to tangibly demonstrate benefits to victims; 5) establish independent monitoring and transparency mechanisms (including public reporting and civic oversight) to sustain public trust.

A further step to enhance the effectiveness and credibility of Syria’s emerging transitional justice institutions would be to establish a formal data-sharing framework between the National Transitional Justice Commission (NTJC), the National Commission for Missing Persons (NCM) and the UN-mandated Independent Institution for Missing Persons (IIMP). Such cooperation, grounded in informed victim consent, strict confidentiality and independent oversight, would serve several purposes. First, it would prevent duplication of investigative efforts and inconsistencies across national and international databases. Second, it would accelerate the identification of the disappeared by enabling secure exchange of genetic, testimonial and documentary evidence. Third, it would strengthen transparency and public trust by linking domestic mechanisms with an internationally recognised body. Finally, a harmonised and victim-centred data system would improve families’ access to truth, reparations and psychosocial support, thereby transforming fragmented documentation into meaningful outcomes for survivors.

Conclusion

Syria’s transitional framework stands at a crossroads: it can either generate institutions lacking legitimacy or evolve into a process capable of healing collective wounds and rebuilding social trust. The outcome will hinge on ensuring inclusion, transparency and coherence between memory, accountability and reform. If grounded in meaningful engagement with victims and designed with strategic realism, Syria’s path could offer an innovative model of transitional justice for the wider region.

[1] The core international crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) are: genocide (article 6), crimes against humanity (article7), war crimes (article 8) and crime of aggression (article 8 bis).

[2] The Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) is a global pro bono law firm providing free legal assistance to parties involved in peace negotiations, drafting post-conflict constitutions, and war crimes prosecution/transitional justice.

[3] United Nations (UN), Guidance note of the secretary-general, “Transitional Justice. A Strategic Tool for People, Prevention and Peace”, 2023, p.2. Available at: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/default/files/document/files/2024/03/202307guidancenotetransitionaljusticeen.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[4] Yvette Stevens, “Transitional justice – Lessons Learned from Sierra Leona” presented at the PILPG 2025 Peace Negotiation Summer School: Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, July 2025 (available at: https://pilpg-trainings.squarespace.com/day-3-transitional-justice-and-accountability)

[5] Igor Lukšić “Case Study: Lessons Learned from Montenegro’s Transition” presented at the PILPG 2025 Peace Negotiation Summer School: Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, July 2025 (available at: https://pilpg-trainings.squarespace.com/post-conflict-state-building-key-concepts-and-perspectives)

[6] Amina Mohamed, “Legal Reforms and Constitution Building” presented at the PILPG 2025 Peace Negotiation Summer School: Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, July 2025 (available at: https://pilpg-trainings.squarespace.com/post-conflict-governance-and-the-rule-of-law)

[7] Amnesty International, Syria: New Government must ensure Truth, Justice and Reparations for the disappeared, 2025. Available at: https://amnesty.ca/human-rights-news/syria-new-government-must-ensure-truth-justice-and-reparations-for-the-disappeared/#:~:text=He%20said%20the%20NCM’s%20core,by%20the%20rule%20of%20law.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] United Nations, OCHR: Transitional justice and human rights, 2025. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/transitional-justice

[10] Joud Monla-Hassan, “Domestic and Locally Owned Transitional Justice and State-Building Processes in Syria” presented at the PILPG 2025 Peace Negotiation Summer School: Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, July 2025 (available at: https://pilpg-trainings.squarespace.com/day-3-transitional-justice-and-accountability#:~:text=international%20conferences—on%20the%20future%20of,and%20grounded%20in%20local%20realities) See also Nousha Kabawat, “To Syria’s New Justice Commissions: Victims Need You Now,” 31 July 2025, emphasizing that the new commissions must explicitly recognize violations wherever they occur, advocate for victims without discrimination or political pressure, ensure genuine independence, and reflect Syria’s full diversity in composition and decision-making so that all victims are represented and heard (available at: https://www.ictj.org/latest-news/syria’s-new-justice-commissions-victims-need-you-now#:~:text=independence%20by%20ensuring%20that%20no,see%20themselves%20represented%20and%20heard)

[11] Paul R. Williams, “Introduction to Post-Conflict State Building: Challenges and Opportunities”, presented at the PILPG 2025 Peace Negotiation Summer School: Post-Conflict Statebuilding and the Case of Syria, July 2025 (available at: https://pilpg-trainings.squarespace.com/post-conflict-state-building-key-concepts-and-perspectives)

[12] Qutaiba Idlbi, Charles Lister, Marie Forestier, Reimagining Syria: A Roadmap for Peace and Prosperity Beyond Assad, in Middle East Institute, 2025. Available at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/reimagining-syria-roadmap-peace-and-prosperity-beyond-assad#:~:text=supported%20by%20a%20clear%2C%20public,framework%2C%20risks%20undermining%20democratic%20progress

Auther’s Bio

Roberta Lazzaro Danzuso holds a bachelor’s in history, Politics and International Relations and is pursuing a master’s in law in Strasbourg with a focus on minority rights. She has over four years of experience in private tutoring. She helps students understand complex historical, political, and legal topics through clear explanations. Based in Catania, she supports learners at different levels.

She can be reached at : roberta.lazzaro15@gmail.com